Happening Now

Omaha: The Effects of Imbalanced Investment

August 14, 2013

Written By Malcolm Kenton

Omaha, Nebraska is the only city that the inaugural Millennial Trains Project journey stops in that I had not previously visited (I had ridden the train through, but had not gotten off). I hadn't thought there was much to Omaha other than the headquarters of the Union Pacific Railroad (one of the nation's big four freight railroads and the oldest federal government-chartered corporation in the US) and several insurance companies. But there is a considerable amount of creative entrepreneurship going on in downtown Omaha, where several former industrial buildings have been repurposed into galleries, shops, restaurants, and a market. But, like Denver, once you get just outside of downtown Omaha, you find a homogenized Sprawlsville built on the back of massively subsidized highway infrastructure fueled by cheap, abundant oil.

We started the day hearing from Anne Trumble of Emerging Terrain, which organized a project to place banners on the side of an abandoned grain elevator on an abandoned freight rail line clearly visible from Interstate 80 just west of downtown. The banners feature works of a variety of artists from across the country on the themes of food, agriculture and transportation. One of the transportation banners is an image of the city skyline composed of photos of people traveling via different modes, in the proportion to which each mode is used by Omahans. Another is a workable map for an Omaha subway system (which has little chance of getting funded). Emerging Terrain has put together two big communal meals within sight of the elevator, which before the banners had not been noticed by most who drove by—built environment white noise.

Trumble is now involved in the planning process for the Belt Line, a proposed light rail line along the abandoned rail right of way that passes the grain elevator, which would connect several major employment centers with the underserved communities of North Omaha (predominantly African-American) and South Omaha (predominantly Hispanic). Also in the plans are an east-west bus rapid transit line that would go across the Missouri River to Council Bluffs, Iowa, the proposed western terminus of a high-speed rail line from Chicago. Explained that the high-speed line won't cross into Omaha because the state of Nebraska is not cooperating in intercity rail planning—it is the only state where what is called the Department of Transportation everywhere else is still called the Department of Highways.

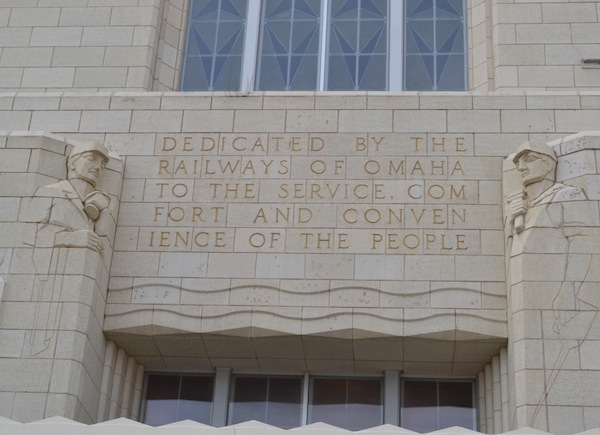

After Trumble's talk at the Kaneko arts space, I walked down to the Omaha Amtrak station, passing the beautiful Art Deco former Omaha Union Station, now a museum of Western heritage. Five of the railroads that once served Omaha stopped their trains at Union Station, while two others stopped across the tracks at the Burlington Station (for the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad). The derelict Burlington Station has just been purchased by a local TV station and is being restored—the Amtrak station is located right next door in a standard-issue building from the late 1970s festooned with the “pointless arrow” logo. I met a 92-year-old gentleman outside the Amtrak station, which was closed, and talked about his experiences with trains.

I then met up with Lance Erickson, who has been a NARP member since the year NARP was founded—1967. He now lives in central Iowa, but lived in Omaha over 20 years ago. As he toured me around town in his rental car (which he festooned with magnets promoting NARP and the Midwest High Speed Rail Association), he commented on how much Omaha has changed in two decades—mostly for the better—though much remains to be done. As we drove out Dodge Street to the auto-dependent strip-mall land of West Omaha, Lance pointed out the vast amounts of government money that has gone into making the car culture possible—money that could otherwise have bought an extensive modern passenger train network.

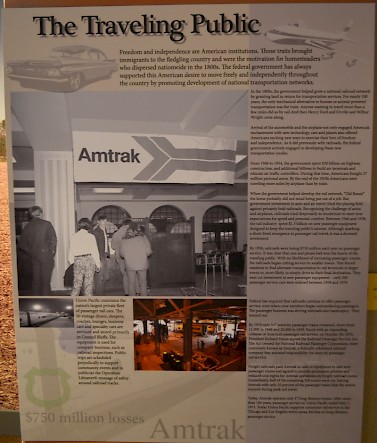

We then drove across the river to Council Bluffs, where we saw several historic railroad sites, including the Golden Spike Monument, marking the “zero mile” where the Union Pacific Railroad began its march westward in 1862, becoming part of the first line to connect coast to coast. We also took a short tour of the Union Pacific Railroad Museum (housed in the former Council Bluffs Public Library) which had an impressive collection and well-designed displays, but unfortunately protrayed passenger train travel as something of the past that is not coming back. The display about the founding of Amtrak had in large type at the bottom “$750 million annual losses,” giving the casual visitor a biased impression of Amtrak's history and purpose.

After dinner and a daily debrief back at Kaneko, Lance drove me back to our private cars—which Union Pacific decided to park at their maintenance facility in West Omaha, a 15-minute drive from downtown, while there were at least two suitable downtown locations at which they could have been parked. At least UP helped make it possible for us to make a stop in a city that could really benefit from proper investment in passenger trains and transit.

-- Malcolm Kenton

"I wish to extend my appreciation to members of the Rail Passengers Association for their steadfast advocacy to protect not only the Southwest Chief, but all rail transportation which plays such an important role in our economy and local communities. I look forward to continuing this close partnership, both with America’s rail passengers and our bipartisan group of senators, to ensure a bright future for the Southwest Chief route."

Senator Jerry Moran (R-KS)

April 2, 2019, on receiving the Association's Golden Spike Award for his work to protect the Southwest Chief

Comments